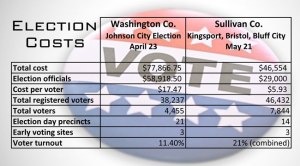

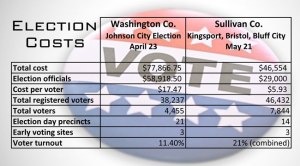

Courtesy of the Johnson City Press

Seldom does a week goes by that I am not asked by a jurisdiction to provide estimates of election costs for a series of hypothetical scenarios under consideration. In the US there is a wide range of costs for an election depending upon the county, the date, the number of participants and the accounting and billing methods used by a county. Providing an estimate is not a science- it is an art form. An estimate must not understate the actual costs that will be billed nor should it greatly overstate the costs. Estimates which are not in-line with the actual costs undermine the credibility of election officials and invites accountants and financial managers to scrutinize the way election costs are calculated, often opening up a window into the bizarre and byzantine

Typical consumer cost models.

We live in a society where the price of almost everything we purchase is pre-determined and not subject to negotiation- with the notable exceptions of real estate and autos. The price of a gallon of milk is clearly marked, doesn’t change from one customer to another and does not change between the trek from refrigerator case to the checkstand. The price doesn’t vary by the number other people buying milk from the same store on the same day. The price per ounce is based upon the contents and not by the portion consumed.

When we take our car to a car wash we pay a fixed price to have it cleaned. We are not charged by the wheel, the number of doors or the number of windows. We are paying for a service- to have our car cleaned and these variables and others such as the amount of water used, the number of rags soiled or the number of people working on the car do not change the price or the value of the service.

Free riders are not welcome in our normal world of business transactions. If a pizza is shared four ways we recognize the inherent unfairness in splitting the cost among only three of the four parties. Similarly, if a person asks to tag along on a road trip and offers only to pay the incremental increase in fuel consumption because, after all everyone else was already will to pay the cost of the fuel for the trip, the request would be difficult to seriously consider.

Typical election cost models.

In contrast, the cost of elections for most jurisdictions is characterized by some or all of the scenarios above. Jurisdictions commit to conducting elections with no idea what the final cost will be and with no ability to control the variables which influence the cost. Elections are seldom viewed as a service with a single price. Rather elections are considered a set of commodities or parts with each charged separately. Some jurisdictions (federal and state, courts) never pay their share of an election and shift the costs to others. Some only pay the direct incremental cost of adding their issue to the ballot; in fact, a recent bill passed by the California legislature (SB 279) specifically prohibits counties from charging the proportional cost a specific district seeking to place a measure on the ballot in 9 counties in 2014.

More complicating factors.

Newspaper headlines often declare extravagant costs for each ballot cast in an election causing outrage and pandemonium. Election costs are incurred based upon the number of voters who might show up and not the number of voters who actually do vote. Elections are like catered parties and their cost is based upon the number of guests. If you invite 100 guests, set 100 places, order 100 meals based upon a cost of $10 per guest, the total cost will be $1,000. If only 13 guests show up the cost to the host is still $1,000 even though the $10 cost per anticipated guest changes to $76.92 for each actual guest. Election costs must always be considered on a potential voter basis and not an actual cost per ballot cast.

Cost comparisons between counties are inevitable as we comparison shop for almost everything in our society nowadays. There is no common regulation or agreement regarding which expenses are billable and how they are calculated. There is no agreed upon formula for how costs are allocated. These realities make comparisons an apples-to-oranges exercise and not an apples-to-apples exercise. Furthermore, even with an apples-to-apples comparison, elections are a monopoly in most places and jurisdictions cannot choose to do business with a cheaper county.

In an effort to shop for better election prices, many local jurisdictions have shifted their elections from odd years, in which there are fewer jurisdictions with which to share the cost, to even years where they hope for a lower cost per voter. The initial result was a savings for some while costs for odd year elections were shifted to those not making the change. The predictable result has been that nearly all jurisdictions in some counties hold their elections in an even year. The result is an obscenely long, cumbersome and costly ballot in even years and no election at all in odd years.

Claims for reimbursement for state mandates, exemptions from certain charges, indirect cost calculations and other local peculiarities further add complexity to the already complex and non-standard practice of estimating and billing election costs.

Some considerations for election cost reform.

The first consideration is broadening the measure of election costs from solely quantifiable fiscal metrics to include some qualitative metrics based upon the founding principles of our nation. The even-year crowding of the ballot obscures candidates in contests further down the ballot. Opportunities to address local issues are drowned out in the in the media blitzes and information overload of federal and state contests. While fiscal costs may be lower, the costs of an uniformed electorate should be considered and weighted more heavily. The cost to the integrity of the election of local officers of voters skipping or abstaining from voting local offices as a result of ballot-fatigue and a lack of information about the candidates should also be a non-fiscal cost consideration.

Some might say that it is naive to propose these qualitative measures since the status quo operates to the advantage of the incumbents who prefer to sneak under the electoral radar either unopposed or by relying in their name recognition advantage. When election glitches occur, it is often these same local officials who pontificate against election administrators from the dais about the “sanctity of the franchise” and invoke the “blood and sacrifice” of those who have fought to protect our form of government. If these are more than opportunistic platitudes, it seems that they should be included in any calculation of the cost of elections.

Second, the election community should consider a fee for service model for estimating and allocating the fiscal cost of elections. When I recently took my car to have the water pump replaced, the service person looked up the year and make of my car and the service to be performed in a database, established by the automotive industry, and told me what they would charge as the labor for the service. The guidelines in the database said that it would take an average of 3.5 units of labor to perform the requested service. The number of units was multiplied by the billable labor rate of the type of person who would do the work. The price would not change whether the mechanic was extremely experience and efficient and replaced the water pump in 1.5 hours or if the mechanic was a rookie and it took six hours.

An election is a service just like replacing a water pump. The service is placing an issue or issues on a ballot which is made available to all eligible voters and the results of the voting are tabulated and reported in an accurate and timely manner. That service is the same in a special election, an even year election, a primary election or an odd year election. In a fee for service model, the cost for the exact same service would not vary because of unrelated and unpredictable reasons.

Just like the mechanic used the variables of year, make and model, and the service to be performed, why can’t the service cost of an election be based upon the number of voters, the number of contests and the type of election (poll or by mail) regardless of the actual expenditure of time and resources?

Such a change would require changing the current, byzantine election cost paradigm and aligning it with the pricing and cost estimating paradigm we operate in on a daily basis. Free-riders would be eliminated. Prices would be predictable. All would pay a rate proportional to size and scope of services. To affect such a change, the cost of elections would have to be standardized across jurisdictional lines.

Is it possible?