[Note: A year and a half after I posted some thoughts on election costs to this blog, I participated in a meeting of election officials as part of this project. The experience harkens visions of the process of calculating election costs as a Rube Goldberg contraption.For those unfamiliar with the expression, Merriam Webster, In 1931, adopted the phrase “Rube Goldberg” as an adjective defined as accomplishing something simple through complicated means.

In the spirit of that image, I thought I would re-post my observations regarding election costs.]

“The bill is just a made-up number. The true problem in health care is we don’t understand our costs. If you don’t know your costs, you can’t drive down health spending in this country.” ~ University of Utah Health Sciences Senior Vice President Vivian Lee (Salt Lake Tribune, December 16, 2013)

This quote might have easily been made about election costs. Last week at the California Election Officials’ New Law Conference in Sacramento, it was announced that the Future of California Elections (FOCE) and the California Association of Clerks and Election Officials (CACEO) received a generous grant from the Irving Foundation to study the cost of elections in California. There were few details offered about the scope, purpose and objectives of the study and no details on either the FOCE website or the Irvine Foundation site which is probably because the grant was recently announced.

The cost of elections has long been an interest of mine. I chaired the Washington State Auditors Association Task Force on Election Costs from 1999-2002. I have defended billing practices from challenges by Elected Officials, Fiscal Officers and Financial Auditors. I have developed, documented and implemented county election cost calculators and billing protocols for a half dozen jurisdictions. I have written legislative proposals, academic papers and even recently blogged on the question of election costs- The Mystery of Election Costs.

It is this long-term interest in election costs that has triggered a myriad of questions about what is(are) the question(s) the research is intended to answer; from which point of view will the issue be considered; about whether policy proposals are intended to be a work product of the study.

How much does that election cost? Sounds like a simple and straight forward question, right? Maybe if you are a member of the public, activist or a scholar.

If you are a county legislator, administrator or budget person you are probably asking questions like: How much was actually expended for the election? How much in addition to previously appropriated funds were expended? How much were local funds? How much was offset by revenue? What is the difference between current expenditures and expected reimbursement?

If you are the entity for whom the election was conducted you are asking: How much are you charging me for this election? What are the indirect costs you are charging me? What is my cost per voter compared to the cost per voter of others or the past? Why is it so much?

If you are someone concerned about the cost of elections with dreadfully low participation rates or someone seeking to sensationalize low turnout you would be asking: What was the cost of each vote cast in the election?

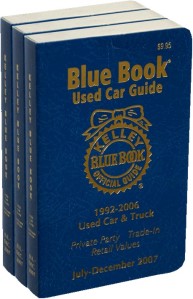

This type of thing should not be very surprising to anyone who has asked, “What does that car cost?” Everyone has heard of the “Kelly Blue Book”, the authoritative guide to pricing a car, but few know that there are different versions with different values depending on who you are and your reason for asking the question. The consumer has one version for private sales which contains high and low values depending on the condition of the car. Most consumers think this is the only book and everyone is working with the same information. Not so. Different versions of the Blue Book are closely held and contain different values based upon whether you are a dealer and reselling a car, a dealer taking a car in trade or an insurance agent calculating salvage or replacement value. The cost of the exact same car, like an election, is calculated based upon the assumptions you make, your reason for asking and the capacity in which you ask the question. The answer is never the same.

Any study of election costs which does not acknowledge these realities can save a lot of time and money and conclude right up front, like health care in the quote above, “The [cost] is just a made up number.”

Stay tuned.